Economics: Economics focuses on the behaviour and interactions of economic agents and how economies work. Microeconomics analyzes basic elements in the economy, including individual agents and markets, their interactions, and the outcomes of interactions. Individual agents may include, for example, households, firms, buyers, and sellers. Macroeconomics analyzes the entire economy (meaning aggregated production, consumption, savings, and investment) and issues affecting it, including unemployment of resources (labour, capital, and land), inflation, economic growth, and the public policies that address these issues (monetary, fiscal, and other policies). See glossary of economics.

Other broad distinctions within economics include those between positive economics, describing "what is", and normative economics, advocating "what ought to be"; between economic theory and applied economics; between rational and behavioural economics; and between mainstream economics and heterodox economics.[5]

Economic analysis can be applied throughout society, in business, finance, health care, and government. Economic analysis is sometimes also applied to such diverse subjects as crime, education,[6] the family, law, politics, religion,[7] social institutions, war,[8] science,[9]and the environment.[10]

The discipline was renamed in the late 19th century, primarily due to Alfred Marshall, from "political economy" to "economics" as a shorter term for "economic science". At that time, it became more open to rigorous thinking and made increased use of mathematics, which helped support efforts to have it accepted as a science and as a separate discipline outside of political science and other social sciences.[a][12][13][14]

There are a variety of modern definitions of economics; some reflect evolving views of the subject or different views among economists.[16][17] Scottish philosopher Adam Smith (1776) defined what was then called political economy as "an inquiry into the nature and causes of the wealth of nations", in particular as:

Jean-Baptiste Say (1803), distinguishing the subject from its public-policy uses, defines it as the science of production, distribution, and consumption of wealth.[19] On the satiricalside, Thomas Carlyle (1849) coined "the dismal science" as an epithet for classical economics, in this context, commonly linked to the pessimistic analysis of Malthus(1798).[20] John Stuart Mill (1844) defines the subject in a social context as:

Alfred Marshall provides a still widely cited definition in his textbook Principles of Economics (1890) that extends analysis beyond wealth and from the societal to the microeconomic level:

Lionel Robbins (1932) developed implications of what has been termed "[p]erhaps the most commonly accepted current definition of the subject":[17]

Robbins describes the definition as not classificatory in "pick[ing] out certain kinds of behaviour" but rather analytical in "focus[ing] attention on a particular aspect of behaviour, the form imposed by the influence of scarcity."[24] He affirmed that previous economists have usually centred their studies on the analysis of wealth: how wealth is created (production), distributed, and consumed; and how wealth can grow.[25] But he said that economics can be used to study other things, such as war, that are outside its usual focus. This is because war has as the goal winning it (as a sought after end), generates both cost and benefits; and, resources (human life and other costs) are used to attain the goal. If the war is not winnable or if the expected costs outweigh the benefits, the deciding actors (assuming they are rational) may never go to war (a decision) but rather explore other alternatives. We cannot define economics as the science that studies wealth, war, crime, education, and any other field economic analysis can be applied to; but, as the science that studies a particular common aspect of each of those subjects (they all use scarce resources to attain a sought after end).

Some subsequent comments criticized the definition as overly broad in failing to limit its subject matter to analysis of markets. From the 1960s, however, such comments abated as the economic theory of maximizing behaviour and rational-choice modelling expanded the domain of the subject to areas previously treated in other fields.[26] There are other criticisms as well, such as in scarcity not accounting for the macroeconomics of high unemployment.[27]

Gary Becker, a contributor to the expansion of economics into new areas, describes the approach he favours as "combin[ing the] assumptions of maximizing behaviour, stable preferences, and market equilibrium, used relentlessly and unflinchingly."[28] One commentary characterizes the remark as making economics an approach rather than a subject matter but with great specificity as to the "choice process and the type of social interaction that [such] analysis involves." The same source reviews a range of definitions included in principles of economics textbooks and concludes that the lack of agreement need not affect the subject-matter that the texts treat. Among economists more generally, it argues that a particular definition presented may reflect the direction toward which the author believes economics is evolving, or should evolve.[17]

Macroeconomics

Macroeconomics examines the economy as a whole to explain broad aggregates and their interactions "top down", that is, using a simplified form of general-equilibriumtheory.[62] Such aggregates include national income and output, the unemployment rate, and price inflation and subaggregates like total consumption and investment spending and their components. It also studies effects of monetary policy and fiscal policy.

Since at least the 1960s, macroeconomics has been characterized by further integration as to micro-based modelling of sectors, including rationality of players, efficient use of market information, and imperfect competition.[63] This has addressed a long-standing concern about inconsistent developments of the same subject.[64]

Macroeconomic analysis also considers factors affecting the long-term level and growth of national income. Such factors include capital accumulation, technological change and labour force growth.[65]

Growth

Growth economics studies factors that explain economic growth – the increase in output per capita of a country over a long period of time. The same factors are used to explain differences in the level of output per capitabetween countries, in particular why some countries grow faster than others, and whether countries converge at the same rates of growth.

Much-studied factors include the rate of investment, population growth, and technological change. These are represented in theoretical and empirical forms (as in the neoclassical and endogenous growth models) and in growth accounting.[66]

Business cycle

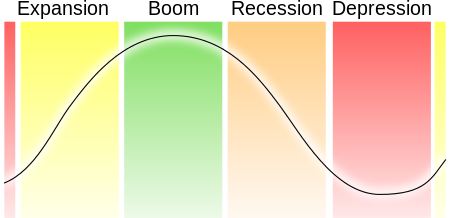

The economics of a depression were the spur for the creation of "macroeconomics" as a separate discipline field of study. During the Great Depression of the 1930s, John Maynard Keynes authored a book entitled The General Theory of Employment, Interest and Moneyoutlining the key theories of Keynesian economics. Keynes contended that aggregate demand for goods might be insufficient during economic downturns, leading to unnecessarily high unemployment and losses of potential output.

He therefore advocated active policy responses by the public sector, including monetary policy actions by the central bankand fiscal policy actions by the government to stabilize output over the business cycle.[67]Thus, a central conclusion of Keynesian economics is that, in some situations, no strong automatic mechanism moves output and employment towards full employmentlevels. John Hicks' IS/LM model has been the most influential interpretation of The General Theory.

Over the years, understanding of the business cycle has branched into various research programmes, mostly related to or distinct from Keynesianism. The neoclassical synthesis refers to the reconciliation of Keynesian economics with neoclassical economics, stating that Keynesianism is correct in the short run but qualified by neoclassical-like considerations in the intermediate and long run.[68]

New classical macroeconomics, as distinct from the Keynesian view of the business cycle, posits market clearing with imperfect information. It includes Friedman's permanent income hypothesis on consumption and "rational expectations" theory,[69] led by Robert Lucas, and real business cycle theory.[70]

In contrast, the new Keynesian approach retains the rational expectations assumption, however it assumes a variety of market failures. In particular, New Keynesians assume prices and wages are "sticky", which means they do not adjust instantaneously to changes in economic conditions.[71]

Thus, the new classicals assume that prices and wages adjust automatically to attain full employment, whereas the new Keynesians see full employment as being automatically achieved only in the long run, and hence government and central-bank policies are needed because the "long run" may be very long.

Unemployment

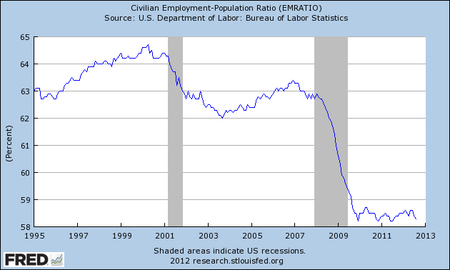

The amount of unemployment in an economy is measured by the unemployment rate, the percentage of workers without jobs in the labour force. The labour force only includes workers actively looking for jobs. People who are retired, pursuing education, or discouraged from seeking work by a lack of job prospects are excluded from the labour force. Unemployment can be generally broken down into several types that are related to different causes.[72]

Classical models of unemployment occurs when wages are too high for employers to be willing to hire more workers. Wages may be too high because of minimum wage laws or union activity. Consistent with classical unemployment, frictional unemployment occurs when appropriate job vacancies exist for a worker, but the length of time needed to search for and find the job leads to a period of unemployment.[72]

Structural unemployment covers a variety of possible causes of unemployment including a mismatch between workers' skills and the skills required for open jobs.[73] Large amounts of structural unemployment can occur when an economy is transitioning industries and workers find their previous set of skills are no longer in demand. Structural unemployment is similar to frictional unemployment since both reflect the problem of matching workers with job vacancies, but structural unemployment covers the time needed to acquire new skills not just the short term search process.[74]

While some types of unemployment may occur regardless of the condition of the economy, cyclical unemployment occurs when growth stagnates. Okun's lawrepresents the empirical relationship between unemployment and economic growth.[75] The original version of Okun's law states that a 3% increase in output would lead to a 1% decrease in unemployment.[76]

Inflation and monetary policy

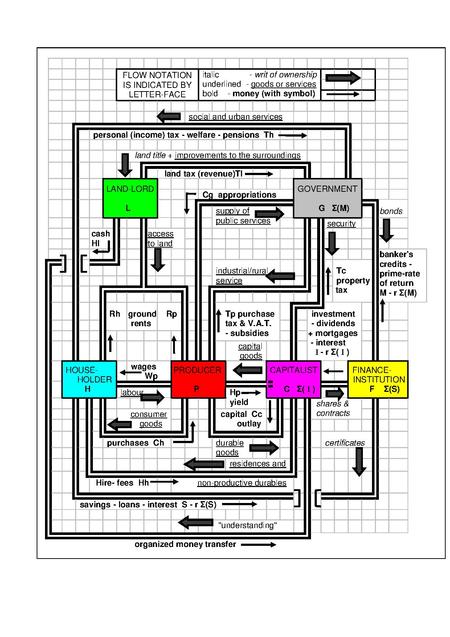

Money is a means of final payment for goods in most price system economies, and is the unit of account in which prices are typically stated. Money has general acceptability, relative consistency in value, divisibility, durability, portability, elasticity in supply, and longevity with mass public confidence. It includes currency held by the nonbank public and checkable deposits. It has been described as a social convention, like language, useful to one largely because it is useful to others. In the words of Francis Amasa Walker, a well-known 19th-century economist, "Money is what money does" ("Money is that money does" in the original).[77]

As a medium of exchange, money facilitates trade. It is essentially a measure of value and more importantly, a store of value being a basis for credit creation. Its economic function can be contrasted with barter (non-monetary exchange). Given a diverse array of produced goods and specialized producers, barter may entail a hard-to-locate double coincidence of wants as to what is exchanged, say apples and a book. Money can reduce the transaction cost of exchange because of its ready acceptability. Then it is less costly for the seller to accept money in exchange, rather than what the buyer produces.[78]

At the level of an economy, theory and evidence are consistent with a positive relationship running from the total money supply to the nominal value of total output and to the general price level. For this reason, management of the money supply is a key aspect of monetary policy.[79]

Fiscal policy

Governments implement fiscal policy to influence macroeconomic conditions by adjusting spending and taxation policies to alter aggregate demand. When aggregate demand falls below the potential output of the economy, there is an output gap where some productive capacity is left unemployed. Governments increase spending and cut taxes to boost aggregate demand. Resources that have been idled can be used by the government.

For example, unemployed home builders can be hired to expand highways. Tax cuts allow consumers to increase their spending, which boosts aggregate demand. Both tax cuts and spending have multiplier effects where the initial increase in demand from the policy percolates through the economy and generates additional economic activity.

The effects of fiscal policy can be limited by crowding out. When there is no output gap, the economy is producing at full capacity and there are no excess productive resources. If the government increases spending in this situation, the government uses resources that otherwise would have been used by the private sector, so there is no increase in overall output. Some economists think that crowding out is always an issue while others do not think it is a major issue when output is depressed.

Sceptics of fiscal policy also make the argument of Ricardian equivalence. They argue that an increase in debt will have to be paid for with future tax increases, which will cause people to reduce their consumption and save money to pay for the future tax increase. Under Ricardian equivalence, any boost in demand from tax cuts will be offset by the increased saving intended to pay for future higher taxes.

International economics

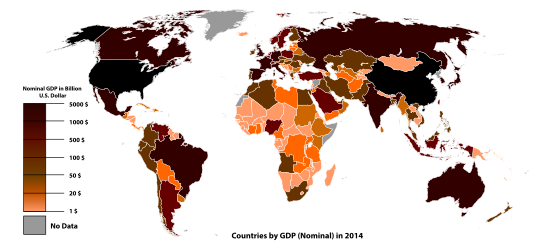

International trade studies determinants of goods-and-services flows across international boundaries. It also concerns the size and distribution of gains from trade. Policy applications include estimating the effects of changing tariff rates and trade quotas. International finance is a macroeconomic field which examines the flow of capital across international borders, and the effects of these movements on exchange rates. Increased trade in goods, services and capital between countries is a major effect of contemporary globalization.[80]

Development economics

The distinct field of development economicsexamines economic aspects of the economic development process in relatively low-income countries focusing on structural change, poverty, and economic growth. Approaches in development economics frequently incorporate social and political factors.[81]

Economic systems

Economic systems is the branch of economics that studies the methods and institutions by which societies determine the ownership, direction, and allocation of economic resources. An economic system of a society is the unit of analysis.

Among contemporary systems at different ends of the organizational spectrum are socialist systems and capitalist systems, in which most production occurs in respectively state-run and private enterprises. In between are mixed economies. A common element is the interaction of economic and political influences, broadly described as political economy. Comparative economic systemsstudies the relative performance and behaviour of different economies or systems.[82]

The U.S. Export-Import Bank defines a Marxist–Leninist state as having a centrally planned economy.[83] They are now rare; examples can still be seen in Cuba, North Korea and Laos.[84][needs update]

Practice

Contemporary economics uses mathematics. Economists draw on the tools of calculus, linear algebra, statistics, game theory, and computer science.[85] Professional economists are expected to be familiar with these tools, while a minority specialize in econometrics and mathematical methods.

Theory

Mainstream economic theory relies upon a priori quantitative economic models, which employ a variety of concepts. Theory typically proceeds with an assumption of ceteris paribus, which means holding constant explanatory variables other than the one under consideration. When creating theories, the objective is to find ones which are at least as simple in information requirements, more precise in predictions, and more fruitful in generating additional research than prior theories.[86] While neoclassical economic theory constitutes both the dominant or orthodox theoretical as well as methodological framework, economic theory can also take the form of other schools of thought such as in heterodox economic theories.

In microeconomics, principal concepts include supply and demand, marginalism, rational choice theory, opportunity cost, budget constraints, utility, and the theory of the firm.[87] Early macroeconomic models focused on modelling the relationships between aggregate variables, but as the relationships appeared to change over time macroeconomists, including new Keynesians, reformulated their models in microfoundations.[71]

The aforementioned microeconomic concepts play a major part in macroeconomic models – for instance, in monetary theory, the quantity theory of money predicts that increases in the growth rate of the money supply increase inflation, and inflation is assumed to be influenced by rational expectations. In development economics, slower growth in developed nations has been sometimes predicted because of the declining marginal returns of investment and capital, and this has been observed in the Four Asian Tigers. Sometimes an economic hypothesis is only qualitative, not quantitative.[88]

Expositions of economic reasoning often use two-dimensional graphs to illustrate theoretical relationships. At a higher level of generality, Paul Samuelson's treatise Foundations of Economic Analysis (1947) used mathematical methods beyond graphs to represent the theory, particularly as to maximizing behavioural relations of agents reaching equilibrium. The book focused on examining the class of statements called operationally meaningful theorems in economics, which are theorems that can conceivably be refuted by empirical data.[89]

Empirical investigation

Economic theories are frequently tested empirically, largely through the use of econometrics using economic data.[90] The controlled experiments common to the physical sciences are difficult and uncommon in economics,[91] and instead broad data is observationally studied; this type of testing is typically regarded as less rigorous than controlled experimentation, and the conclusions typically more tentative. However, the field of experimental economics is growing, and increasing use is being made of natural experiments.

Statistical methods such as regression analysis are common. Practitioners use such methods to estimate the size, economic significance, and statistical significance("signal strength") of the hypothesized relation(s) and to adjust for noise from other variables. By such means, a hypothesis may gain acceptance, although in a probabilistic, rather than certain, sense. Acceptance is dependent upon the falsifiable hypothesis surviving tests. Use of commonly accepted methods need not produce a final conclusion or even a consensus on a particular question, given different tests, data sets, and prior beliefs.

Criticisms based on professional standards and non-replicability of results serve as further checks against bias, errors, and over-generalization,[92][93] although much economic research has been accused of being non-replicable, and prestigious journals have been accused of not facilitating replication through the provision of the code and data.[94] Like theories, uses of test statistics are themselves open to critical analysis,[95]although critical commentary on papers in economics in prestigious journals such as the American Economic Review has declined precipitously in the past 40 years. This has been attributed to journals' incentives to maximize citations in order to rank higher on the Social Science Citation Index (SSCI).[96]

In applied economics, input-output modelsemploying linear programming methods are quite common. Large amounts of data are run through computer programs to analyse the impact of certain policies; IMPLAN is one well-known example.

Experimental economics has promoted the use of scientifically controlled experiments. This has reduced the long-noted distinction of economics from natural sciences because it allows direct tests of what were previously taken as axioms.[97] In some cases these have found that the axioms are not entirely correct; for example, the ultimatum game has revealed that people reject unequal offers.

In behavioural economics, psychologist Daniel Kahneman won the Nobel Prize in economicsin 2002 for his and Amos Tversky's empirical discovery of several cognitive biases and heuristics. Similar empirical testing occurs in neuroeconomics. Another example is the assumption of narrowly selfish preferences versus a model that tests for selfish, altruistic, and cooperative preferences.[98] These techniques have led some to argue that economics is a "genuine science".[99]

Profession

The professionalization of economics, reflected in the growth of graduate programmes on the subject, has been described as "the main change in economics since around 1900".[100] Most major universities and many colleges have a major, school, or department in which academic degrees are awarded in the subject, whether in the liberal arts, business, or for professional study.

In the private sector, professional economists are employed as consultants and in industry, including banking and finance. Economists also work for various government departments and agencies, for example, the national Treasury, Central Bank or Bureau of Statistics.

The Nobel Memorial Prize in Economic Sciences (commonly known as the Nobel Prize in Economics) is a prize awarded to economists each year for outstanding intellectual contributions in the field.

Comments